Reorganizing for Success: Capra Consulting’s Journey Applying Team Topologies Beyond IT Roles

Authors: Therese Engen (consultant), Stein-Otto Svorstøl (consultant and COO), Julie Eldøy (former consultant), Gustav Dyngseth (former consultant), Sondre Brekke (former consultant), Aslak Ege (former consultant and group CEO)

Review by: João Rosa (Independent Consultant and Team Topologies Valued Practitioner)

Capra Consulting, a Norwegian IT consultancy, underwent a reorganization to address challenges in communication and decision-making brought about by growth. At 50 employees and a hierarchical organizational model, we wanted to mitigate the risks of reduced employee participation in our operation and reduced autonomy that might come with growth. We sought inspiration from the Team Topologies book to create a networked organizational structure that emphasized employee engagement, autonomy, and flexibility. By dissolving the Top Management Group and introducing specialized teams, we fostered distributed decision-making and collaborative problem-solving.

Although the implementation process had its share of challenges, such as the time-consuming familiarization of teams and communication issues, the reorganization had positive impacts, including increased employee skill development, a stronger sense of belonging, and enhanced psychological safety. Overall, the adoption of Team Topologies principals, patterns, and practices facilitated the design of a more effective and inclusive organizational structure for Capra Consulting, which has grown to about 100 employees over the last eight years.

Operating context

Capra Consulting was founded in 2005. We are an independent and fully owned Norwegian IT consultancy, with customers from both government and private sectors in Oslo. We have around 100 employees – team leads, agile coaches, front-end and back-end developers, and cloud architects – who strive to develop IT services with a heart and to inspire our customers and the industry as a whole.

The threat to our core values

One of our core values is that every employee should be able to voice their opinion. This was important to us, and was one of multiple factors that helped us grow from 36 employees in 2014 to about 100 in 2023 (see figure 1). The increase represents a remarkable 166% increase over the nine-year period. The annual growth rates fluctuate with extraordinary growth some years, such as 2015 and 2016, which saw increases of over 23%.

In 2020, Capra spun off Liflig as a corporate subsidiary and established a comprehensive corporate group structure to better manage our expanding operations. This led to a slight decrease in Capra's growth of about 7%, due to the transfer of many work relationships to Liflig.

Figure 1: Annual work units and growth from 2014 to 2023.

The company's organic growth made it increasingly difficult to continue to allow any employee to speak out without changing our structure. The scale of this challenge underscored the necessity for innovative organizational strategies to ensure every employee's voice could be heard inside our expanding team.

At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic worked its way across the world, and working from home became the new normal. This brought challenges to team building and communication as we became more distant from each other. We needed to investigate new ways to organize ourselves to maintain the psychological safety that is essential to efficiently work as a team. Here is how we worked through our challenges and restructured the organization.

Initial challenges

We initially organized Capra as a traditional hierarchy, with a top management group led by the CEO. The management roles reflected individual accountability for functions such as HR, Recruitment, Sales, Practices (competence development), and Delivery (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Capra Consulting January 2020 (translated from Norwegian).

Dysfunctional management team

At one point, the management team realized that we no longer worked as a team with joint decision-making, shared goal-setting and follow-up, celebrating wins together, etc. The weekly management meetings served primarily to share information rather than for communally hammering out decisions. Managers ran their responsibilities pretty much separately and those accountable for a function used the meetings only to update the others on their achievements.

Maintaining this nominal management team resulted in significant financial waste and an increased cognitive burden. Waste included the time spent in weekly management meetings, which lasted about an hour, and additional monthly sessions of half a day to a full day for addressing larger issues. We resolved few substantial problems collectively and could have achieved the necessary coordination in much less time. Up to 20% of the team’s total time spent could be seen as unnecessary extra work. This potentially also led to indirect costs associated with inefficient work practices.

We also observed suboptimal flow of both decisions and execution. In the management team, we often felt like bottlenecks; our individual cognitive capacity was the primary driver for organizational capacity, as ownership and accountability had to come from us. Some examples are:

Unnecessary control in planning processes: Recruitment had to seek approval from the management team for the budget of a trip to a larger campus for student recruitment. The management team required explanations and notes on the importance of various budget items and why they had increased since the previous submission. With their expertise, the Recruitment department could have managed this planning entirely on their own, within agreed-upon targets and limits. The details per budget item are unimportant to the management team, which should have discussed no more than the overall cost and estimated impact.

Deciding on a new customer: The management team was greatly involved in deciding if a new customer was worth pursuing, even for low-risk, high-potential clients whose prospective consultants were interested in the engagement. This led to delays and missed opportunities. If the Sales team had been empowered to make these decisions, within certain limits, they could have acted more swiftly and effectively, improving customer acquisition and satisfaction.

Going to a costly conference: Our employees had and still have a personal budget for conferences and other personal development. Some conferences could cost more than an employee budget would allow, and there were extra funds to allow some people to visit these conferences. Asking for these funds was time-consuming and often delayed decision-making. Trusting teams to make these decisions within budget constraints would have streamlined the process and allowed them to take advantage of timely opportunities.

We found that others could best handle most issues, while we in management wanted to discuss targets and limitations for various initiatives. We also found that we might not know enough to discuss these targets and limitations meaningfully without other input.

Scaling issues

A third challenge we faced was the current organizational structure’s inability to scale. We believed that growing further would require us to introduce either departments or a shared middle-management layer, both solutions increasing the distance between employees and decision-making, reducing employee autonomy.

What we were trying to achieve

To address the challenges we faced, we developed the following objectives for the reorganization:

Enable more employees to participate in running the company, leading to both increased employee engagement and better decision-making.

Increase autonomy and flexibility, so the company could become more robust and respond faster to change.

What we did

Introducing a new level in the organizational hierarchy could have helped us achieve our objectives. This would have enhanced our ability to let more people participate in running the company. However, as we noted, this hierarchical structure might impede the flow of decisions. Additionally, when working with our clients, we advocate for self-driven, autonomous teams, along with a "tight, loose, tight" leadership approach. We employ tools such as Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) to help them implement outcome-oriented work processes and organizational designs. These approaches aim to maximize transparency, accountability, autonomy, and alignment. We prefer to apply these same values to our own company, to "eat our own dog food", and a new hierarchical level does not fit into this approach.

Towards a network-centric organization

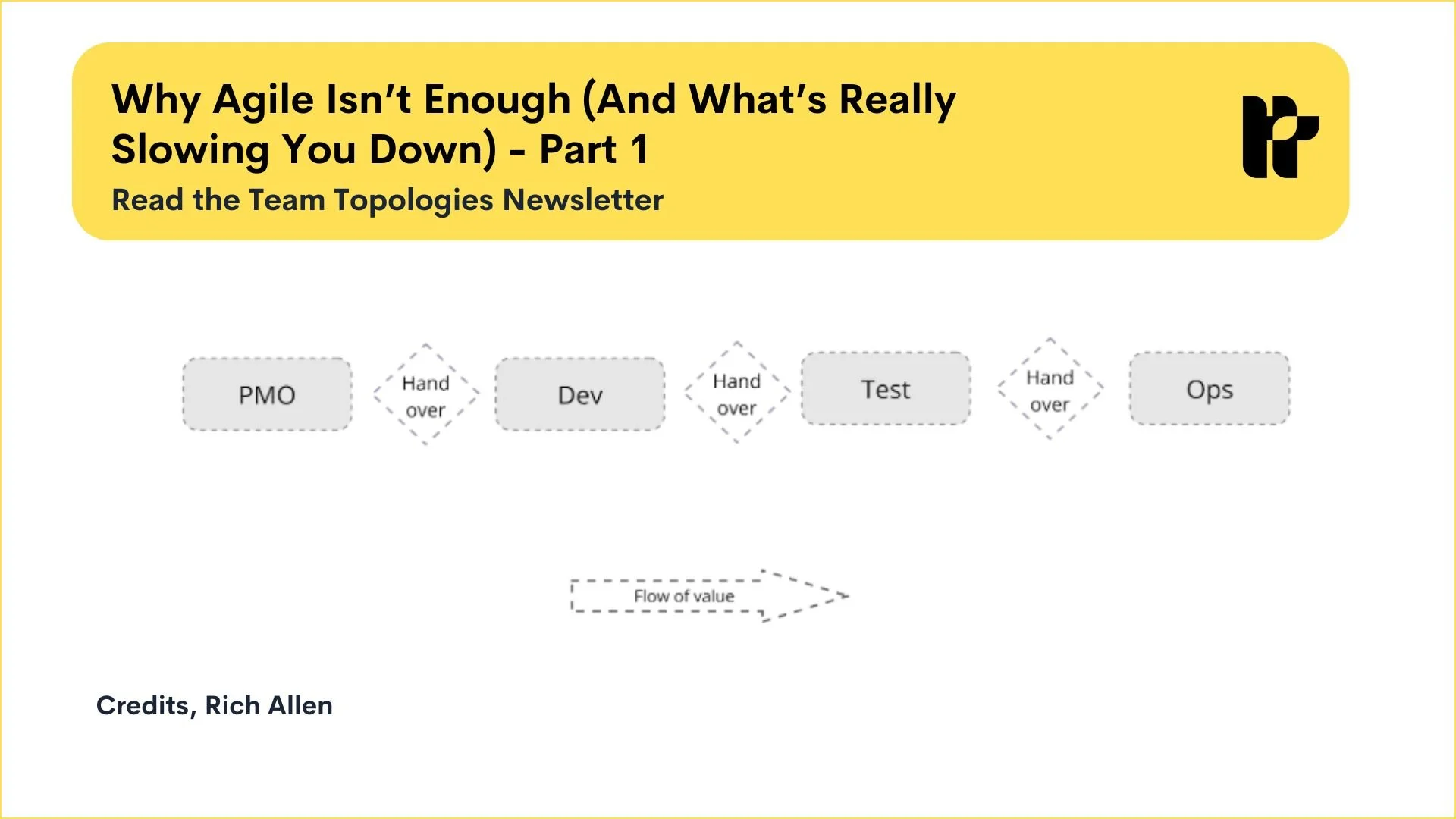

The goal, then, was to transform into a network-centric or actor-oriented organization. Like anyone attempting change, we required a shared mindset and language to effectively discuss the organizational design that would best serve us. While numerous agile development frameworks center on teams, they tend to be extensive and tailored specifically for software development. We sought something more adaptable that could systematize the principles we were already familiar with and provide a common language without being overly prescriptive about the organizational design itself.

Conveniently, Team Topologies (Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais, 2019) aligned perfectly with our endeavors. It builds upon the concepts introduced in Accelerate (Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim, 2018). Skelton and Pais offer a framework for reasoning about team organization within the context of software development – and mention that their principles and topologies can be applied across various contexts, which was an ideal fit for us! Consequently, the book equipped us with the necessary vocabulary to construct a new organizational chart.

In summary, Team Topologies provided us:

four fundamental team topologies, i.e. "team types" and

three fundamental interaction modes for teams, i.e. ways in which two teams can collaborate.

Team for designing the new organization

In May 2020, we started our transformation by establishing a team with the purpose of designing and implementing the new network organizational structure. With our newfound vocabulary from Team Topologies, the team called Team New Organizational Model embarked on an iterative process that looked something like this:

Figure 3: Iterative process for implementing our new organizational structure.

Team blueprint

To support the formation and development of new teams, we crafted a workshop designed to guide them through the initial stages. It is essential that every team possesses a clear and compelling purpose, which serves as the foundation for their existence (Start with Why, Simon Sinek, 2011). This purpose should align with Capra’s broader strategic direction and a team should clearly communicate that purpose within the company. After defining its goals, the team self-organizes and determines the most effective way to achieve its objectives with the available resources.

The process of forming a team should be straightforward, and disbanding it should be equally uncomplicated. To facilitate this, the internal Team New Organizational Model developed a visual representation of the Capra team lifecycle from the inception of an idea to the eventual conclusion of the team’s mission. As shown in figure 4, the lifecycle starts with an idea or a need that someone takes responsibility for. (We should explain that at Capra, we refer to each employee as a “goat”, a nod to the translation of the Latin capra.)

The Capra team lifecycle starts with the ideation phase, progresses through the stages of team formation, and continues as the team works through the forming, storming, and norming phases to become fully operational. A few of the exercises from the forming phase are shown in figures 5 and 6. Upon the successful completion of its mission, the team is safely and systematically disbanded, emphasizing the cyclical nature of team dynamics within the organization.

Figure 4: The Capra team lifecycle, a typical approach (translated from Norwegian).

Figure 5: The Capra team lifecycle, a typical approach (translated from Norwegian).

Figure 6: The Capra team lifecycle, a typical approach (translated from Norwegian).

Dissolving the management team

In September 2020, we decided to dissolve the management team. Despite no clear plan for reassigning the responsibilities and tasks typically handled by this management team, we believed that dissolving the team would create a necessity and expedite the formation of multiple new teams.

By dissolving the management team, we introduced a void in the organizational structure that we needed to fill. This void created a sense of urgency and compelled us to reevaluate our team composition and distribution of responsibilities. It forced us to reconsider traditional hierarchical models and encouraged the emergence of self-organizing teams. Without a centralized management team, the need for distributed decision-making and collaborative problem-solving became paramount.

One example that highlights the need for collaborative problem-solving followed from the Team Technology Leadership’s resounding success at recruitment. This team was first responsible for creating a community of practice within leadership and technology management. To build the community, they wanted to hire more colleagues. All teams operated with OKRs, and this team of technology leaders unsurprisingly consisted of several leaders with strong routines for setting and achieving goals. They chose to handle their own recruitment process instead of delegating it to one of the recruitment teams, aiming to control as much of their goal achievement as possible. The team was highly successful in meeting its recruitment goals, resulting in the hiring of a number of technology leaders unprecedented in Capra’s history. However, the technology leadership team did not account for the need to find assignments for all these new recruits. Team Sales was unprepared for the influx of new technology leaders seeking new and exciting projects. Simultaneously, we faced a post-pandemic market shift, with many companies trimming budgets and putting new projects on hold. This led to a general reduction in available assignments and more idle consultants, which Team Technology Leadership’s earlier collaboration with sales and recruitment could have avoided.

Another example of the need for cross-team solutions emerged during the 2023 company-wide budgeting process. In the original organizational scheme, the management group typically handled this task, but by the end of 2022, there was no management group at Capra. For the 2023 budgeting process, Team Finances and a new Team Strategic Direction took on major roles and were as prepared as they could be. They organized meetings with all teams, encouraging them to set their own budgets for the year. However, Team Strategic Direction and Team Finances did not consider the budgeting knowledge and experience of the teams they encouraged. The budgets involved significant amounts of money and long-term planning, and many teams struggled to find a balance between what they wanted to achieve and what was realistic. Teams set overly ambitious goals, with most believing they could achieve a lot in one year and submitting excessive budget requests. Consequently, the overall company budget was unbalanced and required substantial reductions. The former leaders in Team Strategic Direction and Team Finances did not fully grasp how stressful budgeting could feel, especially for those involved in such activities for the first time. Nor had they adequately communicated to teams that such budget revisions were common in previous budgets and an integral part of the budgeting process.

Figure 7: The evolution of the old model to the new model.

Organizational evolution

The initial organizational map developed by Team New Organizational Model became obsolete due to the ever-changing needs of the organization. As the organization evolves, we create new teams and we disband obsolete ones. This dynamic process ensures that the organizational structure aligns with the current requirements. We initiate the creation of a new team when an individual or a group recognizes the need for one – because they feel the organization lacks something or they have a passion for some unaddressed aspect of the organization. Each employee has the autonomy to propose and establish a team.

Figure 8: The evolution of HR’s operations and strategy functions. The first team for organizational development worked as an enabling team and facilitated activity. It later became a platform team, offering workshops and facilitation as a service.

Conversely, some teams have disbanded as their original purposes became less relevant. For instance, Team Operations initially handled the day-to-day operational tasks, previously managed by the management group, and found that the presence of new teams reduced the volume of these operational responsibilities. These tasks have become more efficiently managed where they happen due to the increased capacity and expertise within the personnel. Additionally, Team Organizational Development has also ended its work as most teams demonstrated effective self-management of their continuous learning. Cross-team learning activities are now handled by Team Strategic Direction (later called “Common Direction”). This evolution can be seen in figure 8.

Recruitment was an area that was formerly a department, and was moved into two teams: Team Junior Recruitment and Team Recruitment and Senior Onboarding for more senior employees. As these teams drew on the competence and capacity of more people and the needs of the organization developed, the configuration of the recruitment teams changed. The evolution can be seen in figure 9.

Figure 9: Evolution of the recruitment teams.

Examples of new teams that are currently active include Team Security responsible for building competence in IT security) and Team Platform and DevEx, which focuses on building communities of practice within platform and development experience. See figure 10 for the current teams.

Figure 10: An overview of all teams and value streams in Capra Consulting November 2020 (translated from Norwegian).

Figure 11: Capra Consulting January 2022 (translated from Norwegian).

How the book helped

Team Topologies presents a leading approach to organizing business and technology teams for fast flow through four fundamental team types and three fundamental modes of interaction for teams. Although the book targets traditional tech companies, the authors believe it is also applicable in other contexts.

Value streams and team APIs

Team Topologies emphasizes the importance of identifying key value streams within the company. At Capra, we identified three value streams: recruiting colleagues, building competency, and selling and delivering services. The book also advocates for shifting responsibilities from individuals to teams, which at Capra has led to the creation of specialized teams like Team Student-Recruitment instead of relying on one person for recruiting summer interns and similar tasks. This evolution is shown in figures 10 and 11.

Additionally, the book introduces the concept of team APIs to enhance team interaction. While the introductory team workshops only partially covered APIs, the significance of these APIs became evident when teams faced communication challenges. We have always used Slack as a communication tool at Capra, and with the formation of new teams, its utility became even more apparent. Each team created its own channel with a standard naming convention. Several teams had both an open channel and an internal channel. Typically, both channels were accessible to everyone, but if someone did not wish to follow all internal team communications, they could choose to participate only in the <team_teamname> channel and not the <team_teamname_internal> channel. Additionally, we created a team_of_teams channel to share common information with all teams.

Several teams established rules and routines for how they preferred others to communicate with them. For instance, Team Finances developed an automated Slack bot to remind all consultants to log their hours at the end of each month. Team Strategic Direction created a bot to remind teams to update their OKRs at the end of each quarter.

Results from our implementation so far

As stated in the beginning of this case study, our goals for the reorganization were to:

enable more employees to participate in running the company, to increase employee engagement and improve decision-making and

increase autonomy and flexibility, in order for the company to become more robust and respond faster to change.

Let’s examine each goal in turn, and any improvements that we’ve seen.

Increased employee engagement and better decision-making

Increased employee engagement

The reorganization led to a higher level of employee engagement and involvement in shaping the company, measured by Officevibe to have moved from 8.2 to 8.4 while the number of employees increased. The number of employees engaged in internal activities also increased. This means we’ve directly achieved our goal of increasing employee engagement. Through qualitative questionnaires, we have discovered strong indications that the increased participation has led to greater productivity, easier launch of new initiatives, and a stronger sense of belonging among team contributors.

Increased opportunity for employees to build additional skills

Establishing multiple autonomous teams and increasing employee engagement has led to what we now consider a strategic capability: employees have the opportunity to build additional skills beyond what normal IT consultancy assignments would provide, in a safe and supporting environment. We believe this will have a positive impact on later career opportunities. For instance, many employees dream of starting their own business at some point, and being part of our Team Finances could be a good place to learn more about the business drivers and economics behind running a company. Other examples include building skills in team leadership, workshop facilitation, strategy development, budgeting, and marketing.

Increased autonomy and flexibility lead to faster response to change

Our qualitative questionnaires reveal that employees find that we provide a lot of autonomy to individuals and to teams. Part of our flexibility is that a team that needs to grow can simply publish on Slack to recruit any employee who might be interested in moving their resources there. We’ve removed obstacles: employees who find an opportunity don’t have to endure a long lead time and teams in need no longer have to spend time navigating other departments as prospective new team members directly contact the team they wish to join. These interactions are usually handled in open Slack channels, so that people outside of the relevant teams can contribute as well.

Additional positive effects from the change

More social arenas

A second positive impact has been the increased number of smaller, more intimate social arenas. Although we are not a large company, feeling a strong connection to 100+ people is difficult, particularly when most of our days are spent with clients. We believe that being part of internal teams boosts the feelings of belonging and common purpose, which are particularly difficult for consultancies to foster. All teams at Capra typically organize their own social gatherings such as shared lunches or dinners. These smaller groups make it easier for teammates to get to know each other than at larger company gatherings. Additionally, being part of multiple teams provides more opportunities to connect with colleagues in various settings.

Increased psychological safety

Another positive result has been a feeling of increased psychological safety. Although we have never cultivated formality, having a management team at all imposes an implicit hierarchy of different levels of importance on employees. The structure of teams feels more equal. And when more people participate in the everyday running of the company, more voices are naturally heard, increasing heterogeneity and fostering a sense of inclusion.

Challenges faced with the new organizational model

After implementing a new organizational design and introducing new teams, we faced unexpected challenges.

Cognitive load

The process of familiarizing the teams with their organizational contexts, roles, and responsibilities took a lot of time. The teams were required to engage in activities such as workshops, team canvases, and wiki pages, which took time away from their primary tasks, increasing pressure and cognitive load. This was particularly overwhelming for employees who were eager to join a team outside of client hours, but lacked a clear understanding of what they were getting into.

The introduction of a new vocabulary and theoretical concepts created a division between those who had read the book and understood the concepts and those who had not, and the latter group lacked confidence in the reorganization.

Unclear responsibilities

As the number of teams increased, so did the number of touchpoints each team regularly had to deal with. They faced questions like "Is this our responsibility or yours?", "Who should I contact?", and "Is there a team that has already solved this problem we’re facing?" In such situations, each team must provide easily accessible documentation that states its purpose, capabilities, services they provide, roadmap, and communication priorities (team APIs). Unfortunately, we didn't prioritize this early enough, resulting in overlapping or unclear responsibilities, especially among teams in the same value stream. This was later mitigated by workshops to establish team APIs.

Lack of vision and continuity

Teams initially operated without a designated team leader. However, we soon encountered issues. For example, response time to inquiries suffered as no one felt accountable for answering them. Meetings lacked productivity due to the absence of a dedicated person responsible for agenda preparation and facilitation. Some teams lacked a cohesive, long-term vision which was particularly challenging when setting OKRs. Consequently, most teams opted to appoint a team leader on a monthly or quarterly basis to address these concerns.

The team's right to exist

As the number of teams in Capra grew, we needed some of them to disband when they recognized that they no longer had a functional purpose. It took a long time for the first team to expire – almost a year. We suppose the lack of established procedures hindered the teams from reflecting on whether they still had relevant responsibilities or whether these better fit other teams. Teams cannot grow indefinitely; excessive communication overhead makes coordination challenging. Who can claim that a team should disband? Is it solely the team’s own decision or can others recommend a team cease operating? Psychological safety should allow anyone with valid arguments and the best interest of Capra's success in mind to suggest the end of a team.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Capra Consulting's reorganization was a strategic move to address communication and decision-making challenges arising from its growth. With 50 employees operating within a hierarchical structure, the firm recognized the potential risks of reduced employee participation and autonomy as the company expanded. Drawing inspiration from Team Topologies, Capra implemented a network-oriented organizational structure that prioritized employee engagement, autonomy, and flexibility. The team structure has developed over time, according to the needs of the organization and the market.

The transition involved dissolving the Top Management Group and forming specialized teams, which encouraged distributed decision-making and collaborative problem-solving. While the implementation faced challenges, such as time-intensive team familiarization and communication hurdles, the positive outcomes were significant. Employees experienced increased skill development, a stronger sense of belonging, and enhanced psychological safety. In total, we achieved what we set out to do: increase employee engagement, improve decision quality, and increase responsiveness. Ultimately, adopting the Team Topologies practices and principles led to a more effective and inclusive organizational structure, supporting Capra Consulting's growth to 100 employees and positioning the company for future success.